- Home

- Andreas Widmer

The Pope & the CEO

The Pope & the CEO Read online

Emmaus Road Publishing

827 North Fourth Street

Steubenville, Ohio 43952

©2011 by Andreas Widmer

All rights reserved. Published 2011

Printed in United States of America

14 13 12 11 1 2 3 4

Library of Congress Control Number: 2011934212

ISBN: 9781931018760

Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture texts in this work are taken

from the New American Bible with Revised New Testament and

Revised Psalms © 1991, 1986, 1970

Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Washington, D.C. and are used by permission

of the copyright owner. All Rights Reserved. No part of the New American Bible

may be reproduced in any form without permission

in writing from the copyright owner.

The Holy Bible, New International Version®,

NIV® Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.™

Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

Revised Standard Version of the Bible—Second Catholic Edition (Ignatius Edition)

Copyright © 2006 National Council of the Churches of Christ

in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

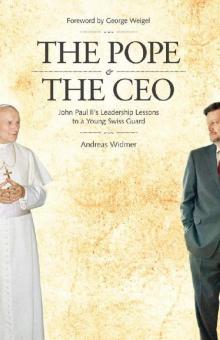

Cover design

Karin Rabensteiner

Layout & Design

Theresa Westling

Cover artwork:

Servizio Fotografico-L’Osservatore Romano

Michelle Widmer–Schultz Photography

For Michelle and Elias

And in homage to Blessed Pope John Paul II

Table of Contents

Foreword

Preface

Introduction

The Pope and I: A Swiss Guard’s Story

Chapter One

Know Who You Are: The Importance of Vocation

Chapter Two

Know God: The Power of Prayer

Chapter Three

Know What’s Right: Ethics and the Human Person

Chapter Four

Know How to Choose What’s Right: Exercising Your Free Will

Chapter Five

Know Where You Are and Where You Are Going: Bridging the Paradox of Planning for the Future yet Living in the Present

Chapter Six

Know Your Team: The Value of Cultivating and Synchronizing Talent

Chapter Seven

Live as a Witness: The Testimony of Right Action

Chapter Eight

Live a Balanced Life: All Things in Moderation

Chapter Nine

Live Detachment: Intentional Humility and Poverty

Conclusion

Back in the Barracks

Acknowledgments

Endnotes

Foreword

Opening the NBC News coverage of Pope John Paul II’s funeral Mass on April 8, 2005, anchor Brian Williams welcomed his audience to “the human event of a generation.” It was an apt phrase, not only because of the vast throngs that had flocked to Rome to say goodbye to John Paul, but because the late pope had touched human lives across a remarkable spectrum of humanity during his twenty-six and a half years as Bishop of Rome.

Andreas Widmer’s was one of the lives John Paul II touched.

Andreas’s own story is a compelling one of faith, success, failure, redirection, and the discovery of what is truly important in a genuinely human life. But I’ll let him tell that story in the fine book you’re about to read. As John Paul II’s biographer, I’d like to highlight several key ideas taught by the late pope: ideas that Andreas Widmer learned (sometimes the hard way) and ideas that he now wants to share with others.

The first of these Big Ideas is that life is vocational. The word “vocation” comes from the Latin verb vocare, “to call,” such that a vocation is a calling. It’s not a career, in the conventional sense of that word. It’s a matter of listening to the promptings of God, and then discerning what unique thing God has in mind for my life. John Paul II was convinced that every human life is a drama, a vocational play in multiple acts, which is playing within the larger cosmic drama of God’s creative, redemptive, and sanctifying purposes. To live life as a vocational drama is to live a bracingly human life—it’s the greatest of human adventures. And, as John Paul taught and Andreas Widmer learned, business can be a real vocation.

The second of these Big Ideas is that things have a purpose, even things that seem random or accidental. Nothing in our lives, John Paul used to say, is a “coincidence.” What seems to be “coincidence” is really an aspect of divine providence that we don’t understand yet. If we can learn to look at our lives in those terms, we’ll never succumb to the most deadening of human temptations—the temptation to boredom.

The third of these Big Ideas involves expectations. From the mid-1990s on, I was constantly asked why Pope John Paul II was such a magnet for young people. One reason, I’m convinced, is that he didn’t pander to the young; rather, he challenged them. In multiple variations on the same great theme, the pope would say, again and again, “Don’t ever settle for anything less than the spiritual and moral greatness the grace of God makes possible in your life. You’ll fail; we all do. But that’s no reason to lower the bar of expectation. Get up, dust yourself off, seek forgiveness and reconciliation, and then keep trying. But don’t ever settle for being less than the noble human being—the leader and exemplar—you can be.”

Christians call that nobility “sanctity,” and the challenge to nobility and sanctity that John Paul II offered was Not-For-Young-People-Only. Why? Because being a saint is every baptized person’s human, as well as Christian, destiny.

When the Catholic Church beatified John Paul II on May 1, 2011, the Church was bearing public witness to its conviction that this was a life of heroic virtue, a life that could be held up for others to emulate. At the same time, the extraordinary response John Paul II drew from men and women who were neither Catholics nor Christians, nor even religious believers, bore testimony to the fact that a saintly life is a compelling human life. The saints are not men and women who have somehow leapt above the human condition; the saints are men and women who have lived fully human lives through the power of grace.

Andreas Widmer is an honest man, a good man, and an insightful man. His reflections on what he learned from perhaps the greatest Christian of our time offer all of us a powerful example of leadership at work.

—George Weigel

George Weigel is Distinguished Senior Fellow of Washington’s Ethics and Public Policy Center, where he holds the William E. Simon Chair in Catholic Studies. His two-volume biography of Pope John Paul II includes Witness to Hope (1999) and The End and the Beginning (2010).

Preface

The Pope & The CEO is a guidebook for people seeking to integrate faith into all aspects of their lives. It is inspired by the example of Pope John Paul II. As a Swiss Guard in my early twenties, I was privileged to live very close to him, one of the great leaders of the 20th century. John Paul’s sincerity impressed me, both in his faith and how he brought that faith to all aspects of his life. His example had a tremendous effect on my life. This book is my effort to share the lessons I learned from his example, based primarily on my memories of John Paul II during the two years I was tasked with protecting him. It also tells the story of how those memories later directed me in my quest to live my Catholic faith as a corporate executive and CEO.

There are biographical and autobiographical elements to this book. Occasional stories are not my own or are ones that I witnessed, along with the rest of the world, through the lens of the media. The book offers glimpses into the life of a Swiss Guard at the Vatican.

The pages tha

t follow, however, are primarily intended to help the Christian executive, CEO, entrepreneur, or small business owner learn some key principles of successful leadership, as I did, at the feet of John Paul II. It is my hope that the head of any organization—family, school, church, or association—will see a ready application, and will benefit from this book and its lessons.

I myself didn’t learn those lessons right away. It took me years to see the connections between the pope I once served and the work I did everyday. I had to make and lose millions of dollars before I began to understand how blessed I was by my time at the Vatican and how much John Paul II had taught me.

This book is the book I wish someone had given me twenty years ago. It makes explicit all the lessons that I had to learn the hard way, through my own failures. It also contains the lessons I’m still learning, lessons that my intellect grasps, but that are more easily understood in theory than lived in practice.

How To Use This Book

The Pope & The CEO is divided into nine chapters or lessons. Each contains several stories or reflections about John Paul II, as well as practical applications and a good dose of Church teaching. I try in each chapter to connect that teaching to the world of business and make it as relevant as possible to the experience of those tasked with leading a team of people, whether big or small.

At the end of each chapter you’ll find a practical exercise, prayer, or piece of wisdom to help you live out the teaching and lessons in your life. You’ll also find questions for reflection designed to help you connect the lessons of the chapter to your own experiences. If you’re interested in learning more, you can visit www.thepopeandtheceo.com, where you’ll find additional exercises, ideas and information on each chapter.

At that same website, you’ll also find recommendations for further reading on each chapter’s subject. You don’t have to be a theologian or a Scripture scholar to understand the teachings outlined in this book. A great amount of background knowledge on the Catholic faith or John Paul II isn’t necessary, but more knowledge is almost always a good thing; if you want to go deeper into any or all of the topics raised here, the reading lists will help you do that.

John Paul’s influence made me understand that business and faith go together—they are not opposed to each other. Business can be a wonderful school of virtue and faith. What’s more, faith and virtue make a business and the economy truly prosperous. The late pope is a great inspiration and example for business leaders. He is that for me and I hope he will be for you as well.

Introduction

The Pope and I:

A Swiss Guard’s Story

It was almost over. I knew that. It was my decision. But it still didn’t feel quite real. For two years, this had been my life, my home, my purpose, and in a few short minutes, it would all come to an end.

Four other guards were with me leaving the service that day. We waited in a small room not far from where the pope held his Wednesday audiences. We heard the noise of the crowds, the cheering and applause. Before long he would be with us, saying goodbye.

I looked around and saw my friend standing next to me. We looked like we belonged to another century—more like something out of a Renaissance painting. Two years before, when I first joined the Swiss Guards, the red, blue, and yellow striped uniform, with its puffed sleeves and full legs, had seemed strange and awkward. It was almost like I was a boy playing dress up. But now it felt familiar, comfortable. I had grown used to it over the course of my service. I’d grown used to everything that had once seemed so strange about living and working in Vatican City. And I was about to walk away from it all.

Then John Paul came in.

In the two years I’d served in the Swiss Guards, I’d seen and talked to Pope John Paul II more times than I could count. But this time was different. This was to be my last audience with him, my final chance to thank him for the opportunity to serve him. I was nervous. I was anxious about the future, anxious that I’d made the wrong decision in choosing to leave the Guards, anxious about the girl who was behind that decision.

When the pope saw me, he pretended to act surprised.

“Didn’t you just start?” he said to me with a smile. “Why are you leaving already? Did I not treat you well?”

“Holy Father, I’m getting older and have to move on,” was my reply.

He looked away and laughed, “Can you believe this guy? Getting old! How old are you?”

“I’m twenty-two.”

“You’re a kid! What are you talking about? Getting old? But if you have to leave, leave with my blessing. Go and bring Christ into the world!”

Go and bring Christ into the world. That was more than just my plan: as a former Swiss Guard, it would actually be my duty.

You see, there’s a code of honor in the Guards passed from generation to generation. When you’re sworn into active duty, you pledge to defend the pope with your life, to shield him with your person. But when you’ve gone back out into the world, it’s understood that you will continue to shield him, only this time with your persona, with how you live your life.

I shook the pope’s hand one last time, suddenly full of confidence. It was his confidence in me, in all of us, that I felt. I looked into his eyes, full of warmth and laughter, and I knew that would be the last time I would ever do so. At that moment, I didn’t want to leave. I wanted to cry. Instead, I walked out of the room. The next day I completed my active service in the Guards, and left to do what the pope asked me to do, what I had in fact sworn an oath to do.

But did I actually do it? Did I bring Christ into the world? Did my actions, in any way, make that holy man I served proud? Or did I let him down?

Twenty years of hindsight tells me that I probably did a little bit of both.

Defenders of the Church’s Freedom

When I first entered the Swiss Guards in December of 1986, I certainly wasn’t thinking about bringing Christ into the world. I was thinking that being a bodyguard was about the coolest job I could imagine.

The possibility of joining the Guards had been proposed to me by one of my friends back in Switzerland. The idea intrigued me. I was nineteen at the time, and not sure what I wanted to do with my life. I’d never been all that crazy about school. Being outdoors was much more my style. But I’d done well with my training in sales and business management, and assumed that would be the direction my career would take.

I wasn’t quite ready to give my life over to business yet. I wanted to do something, to go somewhere outside the small Swiss village where I’d grown up. So I got in touch with an ex-guard and went to his house for dinner. He regaled me with stories of his time in the service, and before the evening ended, I was sold. The opportunity sounded like just what I was looking for. Being Swiss, Catholic, and male, I technically answered every requirement for the job.

There is a bit more to being a Swiss Guard than that. The Swiss Guards are the pope’s personal bodyguards, charged with protecting him in the Vatican and on the road. They’re also responsible for keeping the Papal Palace safe, greeting visitors, and honoring the many important guests who come to the Vatican each year. Accordingly, they need to know the basics of defense strategies, weaponry, and hand-to-hand combat, and any number of details about the Vatican and its protocol.

The Swiss Guards have been performing these duties, in one form or another, since 1506, when 150 men from my homeland first reported to Rome for duty under Pope Julius II. Only a few years later, in 1527, Pope Clement VII named the Swiss Guards “Defenders of the Church’s Freedom” after they saved his life during the Sack of Rome. Making a final stand, 189 Swiss Guards delayed 34,000 troops of Emperor Charles V, so that some of the Guards could bring the pope to safety. They paid a heavy price for their bravery: Only 42 of them survived to enjoy the successful completion of their plan.

Today, there are no invading armies to fend off, but there are still threats to the pope and Vatican City. There also are dignitaries to receive, tourists to man

age, and honor duties to be performed. It all happens in one of the most beautiful cities in the world. How could that not appeal to a young man looking for adventure?

As soon as I finished my one-year service in the Swiss Army (something required of all Swiss men), I entered the Guards.

A World and Church In Flux

I arrived in Rome on December 1, 1986. At the time, John Paul II had been pope for just over eight years. What an eight years it had been. Internally, the Church was still fraught with dissent and conflict left over from both the Second Vatican Council and the cultural revolutions that the West experienced in the 1960s and 1970s. John Paul was under tremendous pressure to “modernize” the Church and bring its teachings in line with the secular culture.

The world was rife with tension in 1986. The Cold War was coming to a head, with America and England, in partnership with the pope, pushing mightily against the Soviet Union. Mikhail Gorbachev had recently come to power, but the Soviet war in Afghanistan still raged, and the U.S. had only just torn down its embassy in Moscow because it was so overrun by bugs…of the electronic variety, that is.

The Pope & the CEO

The Pope & the CEO